Soybeans are the world’s most important source of plant protein and oil; yet how they evolved from wild vines has remained a mystery. Researchers have now found the missing piece—black soybeans served as the bridge between wild plants and today’s yellow varieties.

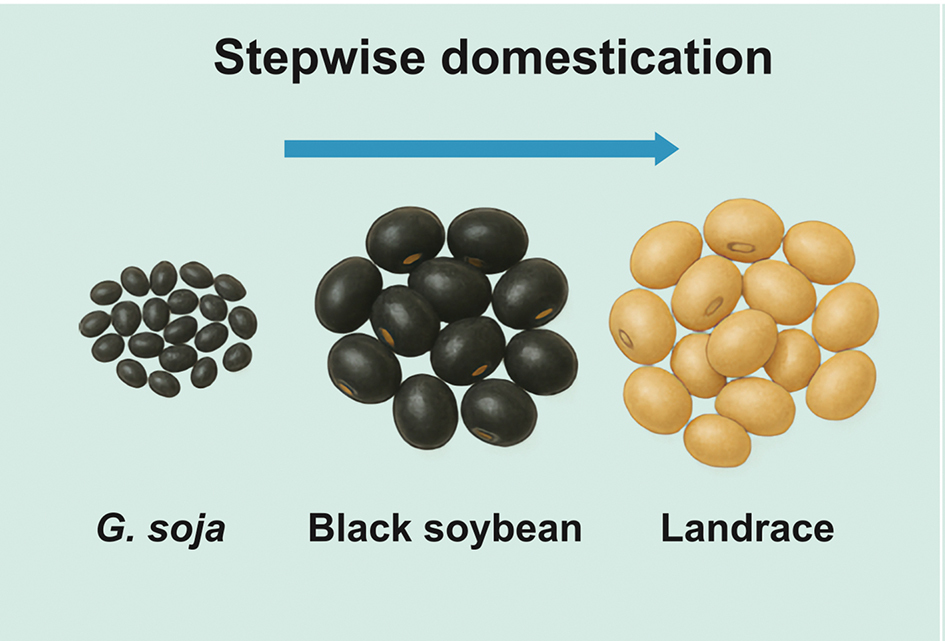

A joint team led by Dr. TIAN Zhixi from Yazhouwan National Laboratory and the CAS Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology analyzed DNA from 8,105 soybean samples to reveal a two-step domestication process, as reported in Cell (doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.09.007) on November 13. Approximately 5,000–6,000 years ago, farmers in two Chinese regions—the Huanghuai Plain and northwest China—first turned wild soybeans into black varieties. They selected for larger seeds, pods that held seeds until harvest, and predictable flowering. Later, farmers refined these black soybeans into yellow types better suited for cooking and storage.

The genetic analysis solved a modern problem. Soybean breeders have long struggled because increasing oil content typically decreases protein, and vice versa. The researchers identified a gene called GmSWEET30a whose specific version can boost both oil and protein simultaneously—potentially breaking this decades-long trade-off.

The study also revealed an unintended consequence of breeding. While creating yellow soybeans, breeders accidentally eliminated genes that provide resistance to crop-damaging pests. These valuable resistance genes still exist in older black soybeans, showing why preserving ancestral varieties matters.

The team created an online database that allows breeders to identify and recover useful traits lost during domestication. By combining ancient genetic diversity with modern techniques, scientists can now develop soybeans that are more nutritious, pest-resistant, and productive.

Black soybeans served as the evolutionary bridge between wild G. soja and modern yellow varieties that now dominate global farms. (Adapted from Zhu et al., 2025)