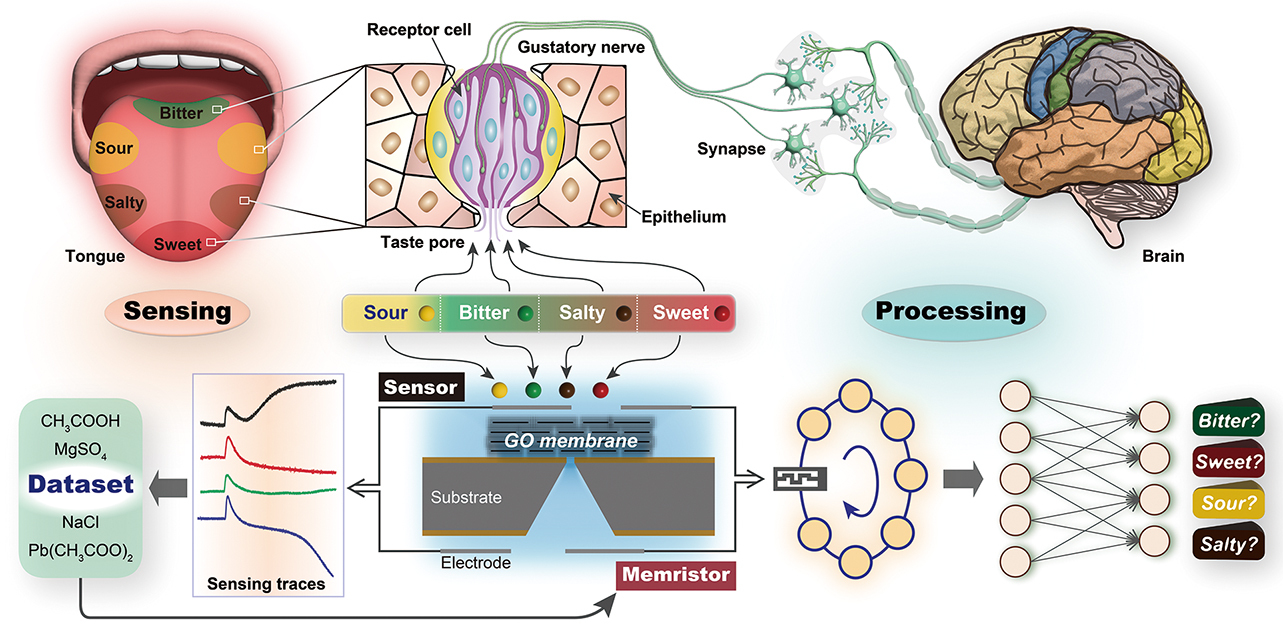

Brain-inspired computer chips can already process visual, auditory, and tactile information, but they have struggled to detect chemicals in wet environments—the way human taste works. This limitation has prevented their uses in medical and environmental fields. As published in PNAS on July 7 (doi: 10.1073/pnas.2413060122), researchers from the National Center for Nanoscience and Technology (NCNST) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences developed an artificial taste system that overcomes this challenge. The team created a device using layered graphene oxide membranes that combines two functions in one—it acts as both a chemical sensor and a learning system that mimics brain synapses.

The key lies in how ions move through tiny channels in the graphene oxide. When ions temporarily get stuck through surface interactions, this creates a memory effect that enables both sensing and information processing. After training with artificial intelligence, the system could distinguish basic tastes like sour, bitter, salty, and sweet, as well as complex flavors such as coffee and cola, with over 90% accuracy. Unlike conventional systems where sensors and processors are separate—causing delays and wasting energy—this device computes where it senses, making it faster and more efficient. The researchers envision that this technology could help restore taste perception in patients who have lost it, enable autonomous machines to analyze their chemical environment, or monitor food and water safety. Future work aims to miniaturize the device for integration into standard computer chips while maintaining performance.

Schematic diagram: human vs. graphene oxide “tasting” system. (Image by NCNST)