By YAN Fusheng

A glimpse of the future granary: The future crops with elite traits will be realized through the convergence of Artificial Intelligence (to predict what to edit), Biotechnology (to perform the edit), and High-Throughput Phenotyping (to verify the result). (Illustration generated by AI)

For millennia, the history of agriculture has been a story of escalating ambition. Human agriculture has evolved from the passive patience of Neolithic domestication to the deliberate, scientific rigor of the first and the second Green Revolutions. Through the systematic cross-pollination of hybrid breeding and the precise, map-based hunts of molecular marker-assisted selection, scientists stopped waiting for nature’s offering long ago; they became active hunters, scouring the genetic landscape for elite traits and shuffling them into our crops.

With the dawn of the CRISPR era in the early 21st century, we grew from hunters to editors. We gained the remarkable ability to correct genetic “typos”, and “knock out” or “knock in” specific genes, revolutionizing our approach for crop breeding. Yet, even as late as 2024, this power remained frustrated by invisible ceilings. We were like authors who could fix a spelling error on page 40 but struggled to rearrange the chapters of the book, or engineers forced to use tools found in nature rather than designing the precise wrench needed for the job. We could edit, yes—but we were bound by the slow churn of plant life cycles and stumbled by the unfathomable errors the editing could incur within the massive genomes.

In 2025, those ceilings were one step closer to being shattered.

Through a series of breakthroughs published in Cell, Science, and Nature, the laboratory of Dr. GAO Caixia at the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, has signaled a transition from editing to architecting. GAO’s team hasn’t just refined a technique; they have integrated artificial intelligence, viral mechanics, and evolutionary biology to dissolve the remaining barriers of plant engineering. They are now able to design molecular scissors with atomic-level precision, trace the evolutionary origins of gene-editing tools to reveal new functional space, reshuffle massive chromosomal structures without leaving a scar, and—perhaps most audaciously—compress millions of years of evolutionary trial-and-error into a few weeks of laboratory time.

“Overcoming limitations requires a paradigm shift,” GAO wrote in a landmark review this year. It was a modest understatement. This is not just a shift; it is the scaling of a new summit.

The Toolmaker’s Forge: AI-Designed Scissors

To engineer a superior plant, one first requires tools of exquisite sharpness. While the genomic editors of the last decade were powerful, they were largely “found” objects—enzymes discovered in nature and repurposed for our needs. They were effective, but often blunt.

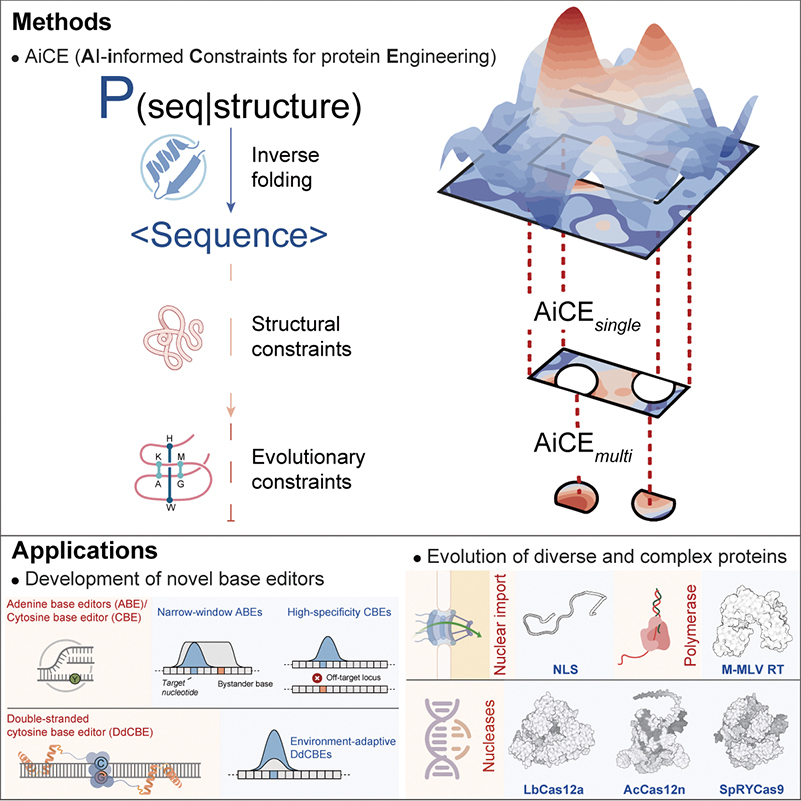

In a Cell study, GAO’s team dismantled this limitation by deploying AiCE (AI-informed Constraints for Engineering). Instead of relying on the laborious screening of random mutations to improve an enzyme, they utilized “inverse folding” deep learning models. The concept is somewhat mind-bending: Instead of predicting a protein’s shape from its sequence, these models work backward, starting from a carefully defined structural backbone tailored to the desired function and then recruiting the precise amino acid sequence needed to fold into that shape.

The results were immediate. Using AiCE, the team optimized “deaminases”—the chemical engines inside Base Editors. They constructed enABE8e, an adenine base editor with a drastically narrowed editing window, and enDdd1-DdCBE, a tool capable of breaching the mitochondrial barrier to edit DNA with 14-fold greater efficiency. This is no longer about finding a tool that might work; it is about computationally designing the perfect tool for the job.

Smarter Protein Engineering: A new AI model uses structural and evolutionary constraints to identify the best possible protein mutations, successfully creating faster and more scalable gene-editing technologies. (Graphic: Fei et al., 2025)

The Evolutionary Bridge: From Selfish Genes to ImmuneScissors

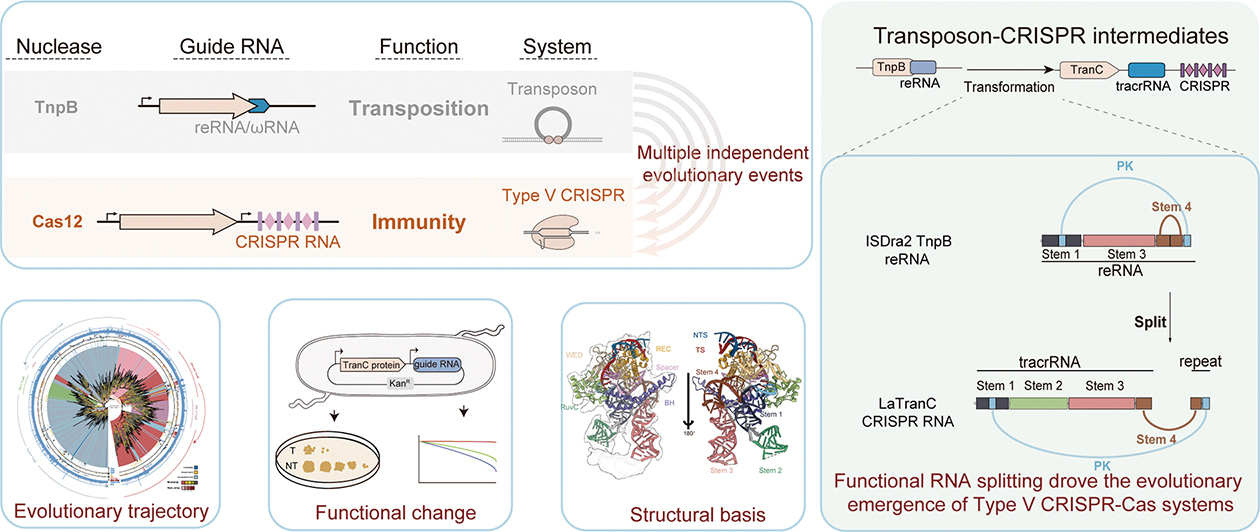

While AI empowers us to perfect nature’s toolkit, evolutionary history offers a vast library of ancestral blueprints waiting to be decoded. In a fundamental discovery published in Cell, Dr. GAO’s team illuminated the origins of the gene-editing tools themselves. They solved the long-standing puzzle of how “selfish” mobile genetic elements (transposons) evolved into the adaptive immune systems (CRISPR-Cas) that researchers rely on today as “gene scissors”.

The team identified “TranCs”—evolutionary intermediates that bridge the gap between the ancestral TnpB nucleases and modern Cas12 effectors. The pivotal innovation was not merely a protein mutation, but a structural revolution in RNA: “functional RNA splitting.” Evolutionary processes split the single transposon guide (reRNA) into two cooperating parts (tracrRNA and crRNA), a shift that birthed CRISPR immunity.

This discovery provided more than just historical insight; it offered a new enzyme reservoir with unique functional features. The team demonstrated that the TranC systems possess “guide RNA interchangeability,” allowing them to function with either transposon-derived or CRISPR-derived RNAs. By leveraging this flexibility, they engineered versatile new editors like eLaTranC, proving that the ancient history of molecular biology is a catalog of parts for future engineering.

Vast Enzyme Reservoir: By tracing the evolutionary transition from transposon-encoded TnpB to CRISPR-Cas12 systems, this study reveals how functional RNA splitting gave rise to immune scissors and offered a new enzyme reservoir for engineering next-generation genome editors. (Graphic: Jin et al., 2025)

Precision Engineering: Moving Mountains

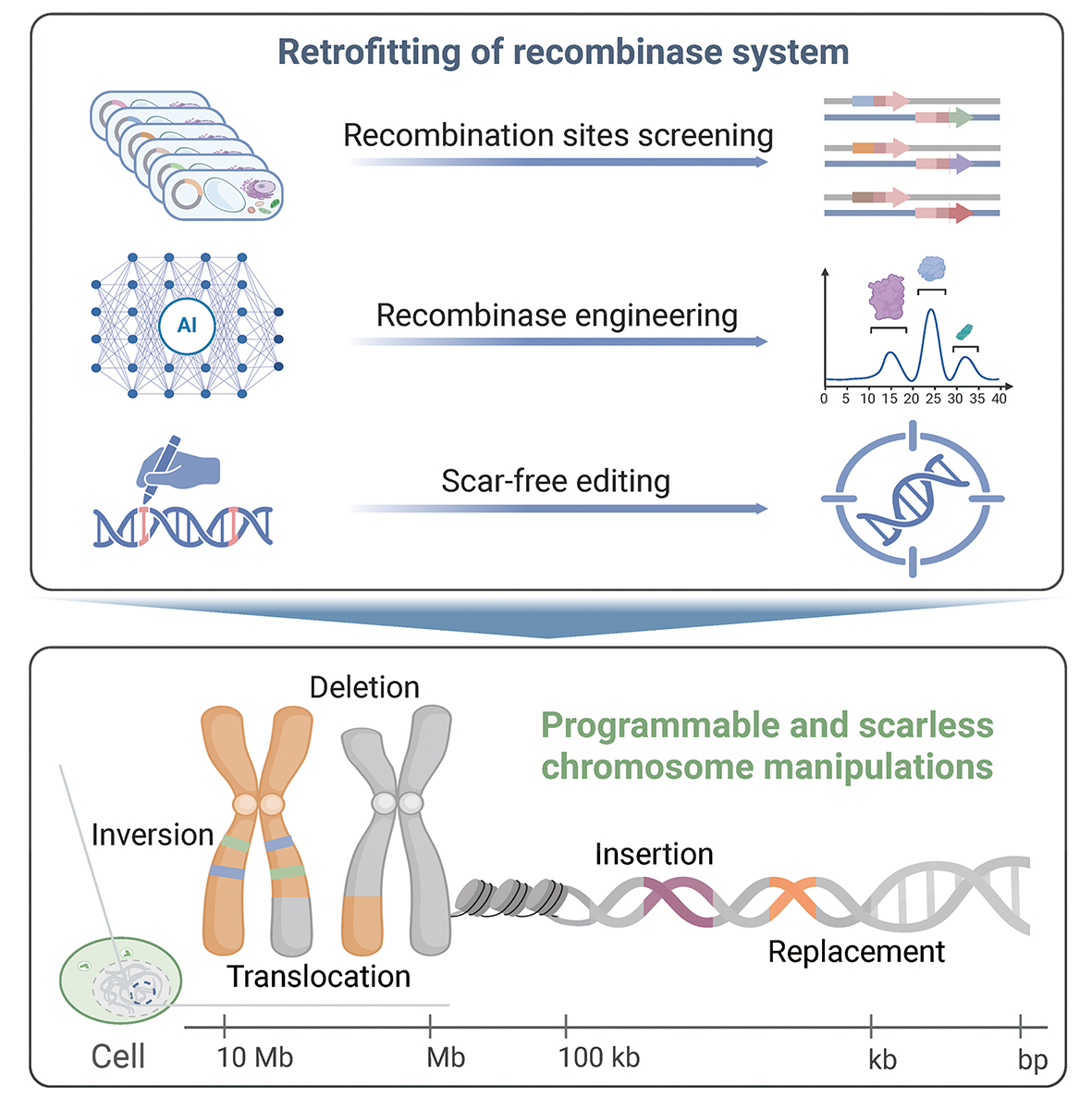

If genome editing technologies in the 2010s were like correcting sentences in a book, chromosome engineering is akin to rearranging the chapters. Many critical complex traits, such as simultaneous drought tolerance and high yield, are not controlled by single genes, but by complex structural variations (SVs) spanning massive genomic regions.

In another breakthrough published in Cell, Dr. GAO’s group unveiled PCE (Programmable Chromosome Engineering), a system that makes the impossible look routine. Historically, moving large chunks of DNA was a chaotic affair, often relying on the cell’s emergency repair pathways which left the genome riddled with errors. The PCE system changes the physics of the problem. It utilizes “Prime Editing” to surgically install landing pads—specific recombination sites—into the genome, and then deploys a designer Cre recombinase to accurately cut and paste the DNA between those pads.

Scalable Genome Engineering: Newly engineered iterative recombinase technologies enable programmable and seamless chromosome editing from kilobase to megabase scale across diverse genomes. (Graphic: Sun et al., 2025)

Warping Time: Evolution in Weeks

Perhaps the most futuristic of GAO’s 2025 achievements is the ability to compress the timeline of evolution itself.

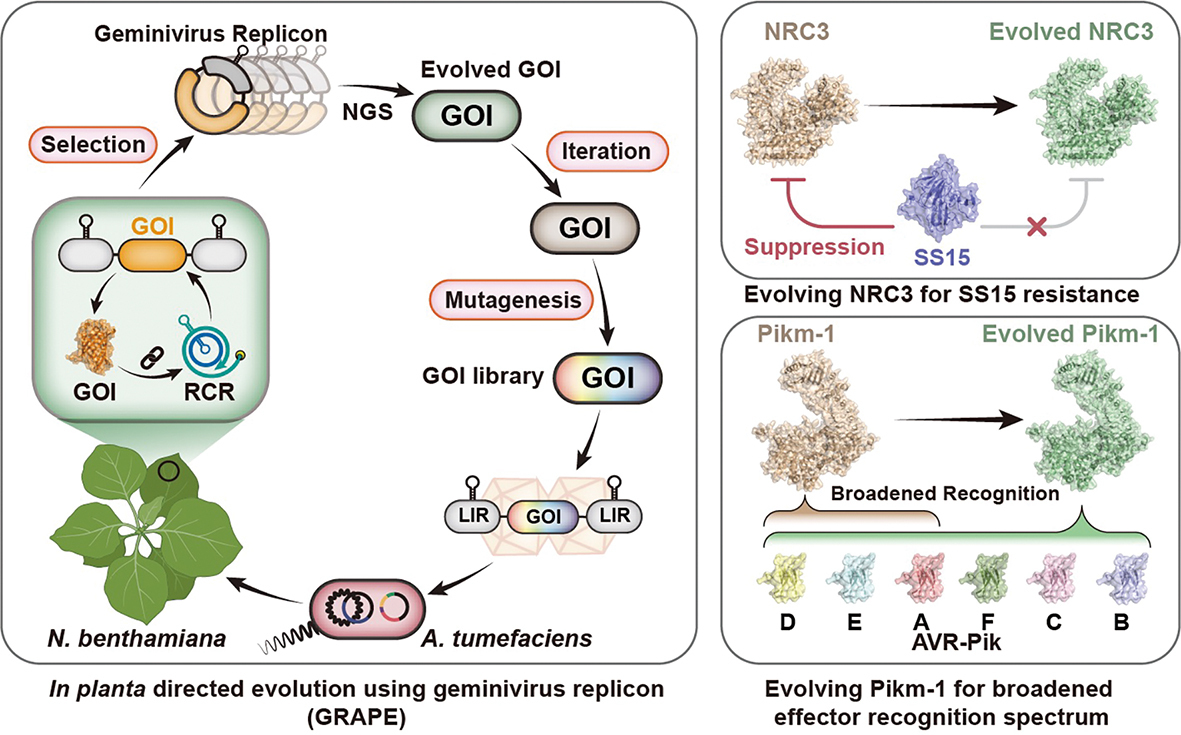

Directed evolution—mutating a gene millions of times to stumble upon a better version—is a standard practice in fast-reproducing bacteria. But for plants, with their months-long life cycles, it has been mathematically impossible. This changed with the introduction of GRAPE—a high-throughput platform described in a recent Science paper as short for the “geminivirus replicon–assisted in planta directed evolution.”

Directed Evolution in Planta: GRAPE harnesses geminiviruses for rapid plant-based evolution. Here, it evolves immune receptors to bypass effector suppression and detect a wider range of pathogens. (Graphic: Zhu et al., 2025)

The team harnessed Geminiviruses, pathogens that replicate with furious speed inside host cells, turning them into vehicles for creation. They loaded gene libraries into these viral replicons and infected the tobacco plants. As the viral replicon multiplied, the genes mutated and evolved inside the living leaf, subjecting the plant to a localized, hyper-accelerated evolutionary pressure.

The implications are profound. They evolved a rice immune receptor, Pikm-1, to recognize not just three, but six different variants of a rice blast fungus effector. By doing so, they effectively compressed the millions of years of the evolutionary “arms race” between plant and pathogen into a few weeks of bench work. This opens a highway for updating crop immunity that could be faster than pathogens can mutate to evade it.

The Harvest: Crops for Human Health

The ultimate test of these technologies is the food on our plates. In a study published in Cell (“Design of CoQ10 crops based on evolutionary history”), the team moved from tool-building to nutritional biofortification.

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) is a potent antioxidant essential for human heart health, usually sold as expensive supplements because most staple crops produce very little of it. Instead, plants produce a related molecule, CoQ9.

By analyzing the evolutionary history of 134 plant species, the team realized that the difference between producing CoQ9 and CoQ10 came down to a single amino acid residue in the Coq1 enzyme (position 240).

Using their precise genome editing tools, they swapped a set of key amino acids centered on this residue in the genomes of rice and wheat. As a result, they turned rice and wheat plants into bio-factories for CoQ10. This proved that by understanding the “evolutionary logic” of a plant, we can use gene editing to restore or enhance ancient nutritional traits, turning our staple foods into functional medicines.

Evolution-Guided Metabolic Engineering: By swapping a single amino acid based on evolutionary history, gene editing transforms rice and wheat into bio-factories for the heart-healthy antioxidant CoQ10. (Graphic: Xu et al., 2025)

The Roadmap: A New Convergence

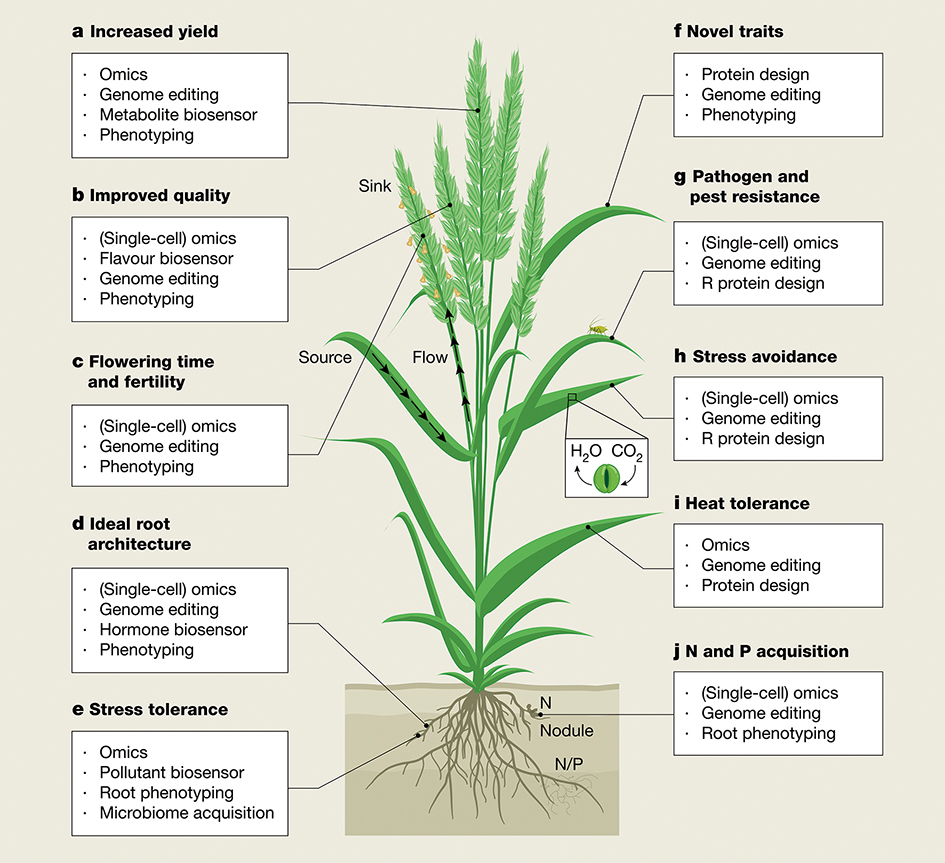

In their review for Nature titled “Integrated biotechnological and AI innovations for crop improvement,” GAO and her co-authors lay out a roadmap for the next decade. It is a vision of convergence.

The authors detail four pillars of innovation that are currently being supercharged by AI to overcome the limitations of natural genetic resources:

● Advanced Omics & Pangenomics: Moving beyond single reference genomes, researchers are now utilizing AI-aided assembly to create telomere-to-telomere (T2T) pangenomes. This allows for the capture of previously elusive structural variations—larger than 50 bp—which are key drivers of phenotypic diversity and stress tolerance.

● Precision Genome Editing: Technologies have evolved from simple CRISPR-Cas9 knockouts to sophisticated tools like base editing, prime editing, and chromosome engineering. These tools enable the fine-tuning of gene expression by modifying upstream open reading frames (uORFs) and cis-regulatory elements (CREs).

● De Novo Protein Design: AI models like AlphaFold 3 and RFdiffusion are now being used to design entirely new proteins. These include custom-designed R proteins for disease resistance and smart biosensors that allow real-time monitoring of plant metabolites and hormones.

● Multimodal Phenotyping: Using a combination of satellites, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and gantry systems equipped with light detection and ranging (LiDAR) and hyperspectral sensors, breeders can now quantify 4D photosynthetic characteristics and complex root architectures in situ.

The future of agriculture lies at the intersection of Artificial Intelligence (to predict what to edit), Biotechnology (to perform the edit), and High-Throughput Phenotyping (to verify the result).

Integrating Emerging Technologies: Each panel identifies specific tools—such as omics, genome editing, and protein design—tailored to enhance traits across different plant organs. (Graphic: Li et al., 2025)

“AI-aided crop design aims to rationally integrate elite alleles into crop genomes,” the authors conclude. This is no longer just about feeding a growing population; it is about “designing” food systems that are climate-resilient, nutritionally complete, and environmentally sustainable. However, the success of this vision hinges on addressing public concerns regarding biological safety and navigating the global regulatory landscape.

To mitigate potential risks, robust technical safeguards are being integrated into the crop improvement pipeline. Scientifically, researchers are implementing precision control systems—such as inducible promoters, logic gates and uORFs—to ensure that engineered traits or designed proteins are expressed only under specific conditions, such as during a pathogen attack, thereby minimizing unintended effects.

These technical advancement are complemented by a shift in global oversight. Regulations for the agricultural application of genome editing have become more relaxed compared to those for transgenic crops in countries such as China, India, and the USA, extending beyond simple point mutations to various types of genetic modifications. Even in regions where transgenic crops remain highly restricted, such as Europe and New Zealand, new regulatory proposals for genome-edited innovations are inspiring optimism about the widespread adoption of these technologies.

As highlighted by Dr. GAO and her colleagues in their Review published in Nature: “Indeed, the increasing rate of regulatory approvals and de-regulations of genome-edited crops highlight a growing global interest in these technologies.”

References

Fei, H., Li, Y., Liu, Y., Wei, J., Chen, A., & Gao, C. (2025). Advancing protein evolution with inverse folding models integrating structural and evolutionary constraints. Cell, 188(17), 4674-4692.e4619. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.06.014

Jin, S., Zhu, Z., Li, Y., Zhang, S., Liu, Y., Li, D., …. Gao C. Functional RNA splitting drove the evolutionary emergence of type V CRISPR-Cas systems from transposons. Cell, 2025, 188(22):6283-6300.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.09.004

Li, G., An, L., Yang, W., Yang, L., Wei, T., Shi, J., . . . Gao, C. (2025). Integrated biotechnological and AI innovations for crop improvement. Nature, 643(8073), 925-937. doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09122-8

Sun, C., Li, H., Liu, Y., Li, Y., Gao, R., Shi, X., . . . Gao, C. (2025). Iterative recombinase technologies for efficient and precise genome engineering across kilobase to megabase scales. Cell, 188(17), 4693-4710.e4615. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.07.011

Xu, J. J., Lei, Y., Zhang, X. F., Li, J. X., Lin, Q., Wu, X. D., . . . Chen, X. Y. (2025). Design of CoQ10 crops based on evolutionary history. Cell, 188(7), 1941-1954.e1915. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.01.023

Zhu, H., Qin, X., Wei, L., Jiang, D., Zhang, Q., Wang, W., . . . Gao, C. (2025). Engineered geminivirus replicons enable rapid in planta directed evolution. Science, 390(6774), eady2167. doi: 10.1126/science.ady2167