Headline · 18 Sep 2025

Scaling Up Mainstreaming Biodiversity through National Park Reforms in China

Scaling Up Mainstreaming Biodiversity through National Park Reforms in China

ZHANG Zhia,b,1, KONG Weilongc,d, ZHANG Huizhie,*,SHI Xiaof, HUANG Baoronga,b,2,*

a. Institutes of Science and Development, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China

b. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 101408, China

c. School of Public Administration and Policy, Renmin University of China, Beijing 100872, China

d. Department of Building and Real Estate, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, 999077, China

e. Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, Beijing 100097, China

f. China International Engineering Consulting Corporation, Ecological Technical Research Institute (Beijing) Co., Ltd., Beijing 100049, China

Abstract: Biodiversity mainstreaming remains among the most persistent gaps in global environmental governance. China’s national park reforms provide a large-scale empirical test of mainstreaming in practice. By unifying fragmented protected areas, consolidating governance mandates, aligning cross-sector policies, and formalizing inclusive stewardship, the reforms have delivered measurable gains in flagship species recovery, ecosystem service resilience, and community participation. Yet its transformative potential is constrained by limited penetration into non-conservation sectors, uneven adaptive capacity, and incomplete social integration. We distill three transferable principles—coherence, consolidation, and co-production—and outline instruments to embed biodiversity imperatives beyond protected areas into infrastructure, agriculture, and regional planning. Achieving the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework will require moving beyond isolated conservation enclaves toward integrated policy ecologies that can durably reconcile biodiversity outcomes with equitable human well-being.

Keywords: biodiversity mainstreaming; protected area expansion; policy integration; community governance; co-management

Cite this article as: ZHANG Zhi, KONG Weilong, ZHANG Huizhi, SHI Xiao and HUANG Baorong. (2025) Scaling Up Mainstreaming Biodiversity through National Park Reforms in China. Bulletin of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, 39, 2025001. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1051/bcas/2025001

Mainstreaming biodiversity—integrating conservation and sustainable use into the core logic of national policy, economic planning, and territorial governance so as to reverse biodiversity loss, restore ecosystems, and support climate-change adaptation, has emerged as a decisive frontier in the global sustainability agenda (Pörtner et al., 2023; Whitehorn et al., 2019). Achieving this shift requires structural reforms that embed biodiversity imperatives across state decision-making. The rationale is clear—without embedding ecological objectives into the institutions that shape land, water, and resource use, conservation will remain peripheral and vulnerable to competing priorities. Yet, in practice, progress has been slow and uneven. Across industrialized and emerging economies alike, biodiversity conservation efforts often remain underfunded, fragmented across agencies, and subordinated to short-term growth imperatives (Xu et al., 2021). The Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’s 30×30 target crystallizes the urgency to break this inertia. It calls for more than expansion of protected areas, and demands structural reforms that embed biodiversity objectives across the routines of state decision-making (Eckert et al., 2023; Maxwell et al., 2020). This is a challenge China shares with the rest of the world.

Against this backdrop, China’s national park reforms, initiated in 2015 as a flagship of its ecological civilization vision, constitute one of the most ambitious governance experiments in contemporary conservation. While their institutional design differs from UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB), the underlying pathways are notably convergent, both seek to reconcile human development and ecological resilience through systems integration and adaptive governance, and learning-by-doing (Folke et al., 2016). Over decades, the global evolution of biosphere reserves and China’s protected area reforms have unfolded as parallel, mutually illuminating processes. Each has informed the other’s thinking on how to align biodiversity conservation with livelihoods, cultural continuity, and territorial planning. In essence, both embody a co-production ethos that generates shared knowledge, governance innovations, and management models (Barraclough et al., 2023; Bridgewater, 2016) capable of translating the idea of living in harmony with nature into practices.

This article positions China’s national park reform as a policy testbed for scaling up biodiversity mainstreaming in complex socio-ecological contexts. Drawing on the early evidence of the officially designated parks, we examine how spatial consolidation, institutional realignment, cross-sector policy integration, and community empowerment have been mobilized to reframe conservation as a developmental priority. By situating these reforms within global debates on governance innovation, we aim to distill lessons and cautions for countries seeking to transform the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework from aspirational targets into embedded governance practice. The sections that follow unpack the reforms’ mechanisms, assess their ecological and social outcomes, identify remaining bottlenecks and explore the strategic frontiers for advancing biodiversity mainstreaming at scale.

Paths to Mainstreaming

China’s national park reforms took shape against a backdrop of entrenched governance fragmentation and accelerating demands for the transformation toward sustainable development. Before 2015, conservation responsibilities were scattered across multiple agencies, producing overlapping jurisdictions, mismatches with ecological boundaries, and weak enforcement (Huang et al., 2018). Despite the rapid proliferation of protected areas, biodiversity decline persisted, revealing systemic flaws in spatial planning, institutional coordination, and policy coherence (Li et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2017). The shift toward building an ecological civilization, coupled with the momentum of the global 2030 Agenda, has created both the political mandate and the normative expectation for a more integrated, system-wide approach to biodiversity governance. Within this context, the national park system has been conceived as a flagship wave of reforms—an institutional redesign intended to unify conservation efforts and embed biodiversity objectives directly into national development strategies.

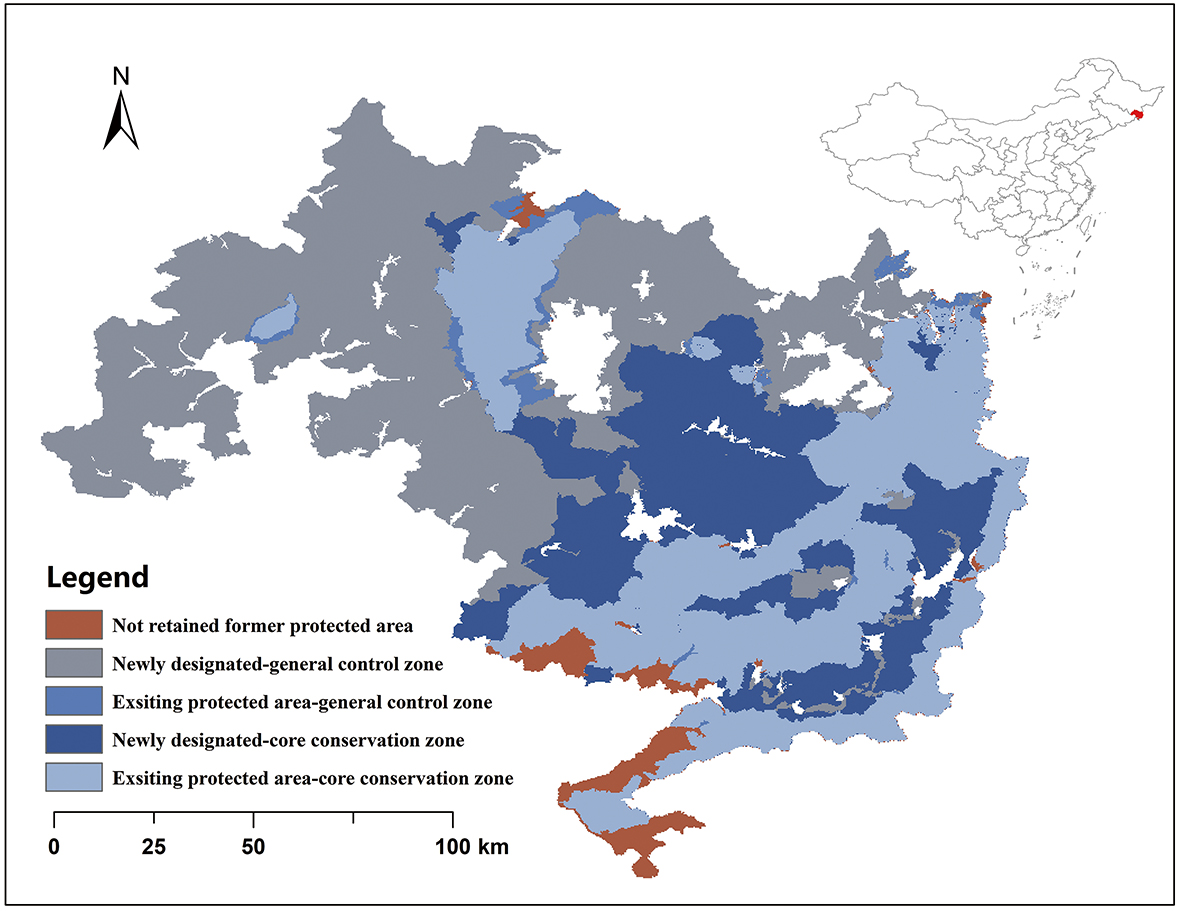

Spatial integration is foundational. The reforms have merged ecologically critical areas previously scattered across nature reserves, forest parks, and scenic sites into unified spatial units defined by ecological integrity rather than administrative convenience (Xu et al., 2019). This consolidation process has reduced the number of protected areas nationwide from 9,240 to 6,736, while expanding the total area by 3.22 million ha (Cheng, 2024). Re-zoning has prioritized landscape-scale connectivity, introduced functional zoning (core conservation zones and general control zones, Fig. 1), and enabled coordinated, ecosystem-based management. By aligning conservation boundaries with natural processes, the reforms have established a spatial infrastructure capable of sustaining long-term biodiversity outcomes.

Institutional consolidation addresses a chronic “multiple brands, no owner” problem. Centralized management under newly created national park administrations—independent of sectoral ministries—has eliminated jurisdictional overlap and clarified the division of responsibilities between central and local governments (Zhang et al., 2017). Integrating ecological monitoring, enforcement, tourism management, and community engagement within a single governance body has shifted the model from fragmented custodianship to unified social-ecological stewardship (Wu et al., 2020).

Fig. 1. Spatial integration between national parks and existing protected areas in the Northeast China Tiger and Leopard National Park. (Map Approval Number: GS(2024)0650)

Policy coordination has elevated national parks to the strategic core of China’s ecological modernization agenda. High-level political endorsement, iterative experimentation through pilot sites, and emerging legal codification, including the draft National Park Law (Yang, 2024), have anchored these reforms within the country’s policy architecture (Zhang et al., 2023). This layered approach marries short-term reform pragmatism with long-term legal stability, creating the conditions for biodiversity goals to permeate sectors such as infrastructure, agriculture, tourism, and finance.

The reformed resource reallocation has ensured that governance mandates are matched with implementation capacity (Xinhua News Agency, 2024). Personnel from disparate agencies have been consolidated into unified teams, supported by targeted training. Central budgetary allocations and fiscal transfers have secured operational stability (Zhang et al., 2024), while investment in ecological big data, remote sensing, and digital monitoring platforms have enhanced evidence-based decision-making and public transparency.

Collectively, these transformations have built an institutional scaffold for embedding biodiversity considerations into the broader machinery of governance, land-use regulation, and development planning. While still in its early stages, the reforms already offered a rare example of state-led, system-wide institutional transformation, one that begins to address the central challenge underscored in the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework—how to turn biodiversity commitments into durable governance systems that can withstand political cycles, sectoral competition, and socioeconomic change.

Progress in Practices

In less than a decade, China’s national park reforms have begun to show measurable ecological and social outcomes associated with mainstreaming biodiversity through system-wide governance change (Wang et al., 2024). These early outcomes provide an important testbed for the kind of transformative approaches envisioned in the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

Flagship species and population rebounds

As a result, consolidation of fragmented reserves, restoration of ecological corridors, and reduced human disturbance have improved habitat integrity, reconnected migration routes, and enabled the recovery of keystone and umbrella species long constrained by administrative fragmentation and degradation. During the pilot (2015–2020) and formal establishment (2021–present) phases, targeted restoration and corridor construction coincided with documented rebounds in multiple flagship species, as reported by Biodiversity Conservation in China (The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, 2021). Giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) population has increased from 1,114 in the 1980s to 1,864 today, supported by a near-doubling of suitable habitat since 2012 and the establishment of the 22,000 km2 Giant Panda National Park, which now shelters 72% of the wild population and has underpinned the species’ IUCN status shift from Endangered to Vulnerable. By 2023, the populations of Amur tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) and Amur leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis) in Northeast Tiger and Leopard National Park increased from 27 and 42 in 2015 to approximately 70 and 80, respectively, with 20 tiger and 15 leopard cubs and survival rates improved from 33% to nearly 50% (Zhang et al., 2025). Hainan gibbon (Nomascus hainanus), once reduced to <10 individuals in two groups, now numbers 35 across five groups. In Sanjiangyuan National Park, snow leopards (Panthera uncia) are now estimated to exceed 1,200 individuals, while Tibetan antelope (Pantholops hodgsonii) have rebounded from fewer than 20,000 to over 70,000 (Wu, 2023). These recoveries illustrate how governance integration, coupled with species-focused management and restored connectivity, can yield rapid biodiversity gains even for species in long-term decline.

Ecosystem services recovery

Beyond species-level gains, the reforms have coincided with measurable recoveries in key ecosystem services, reversing declines that persisted for decades. Remote sensing and biophysical modelling reveal consistent improvements in soil retention, water regulation, and climate buffering capacity across national parks. In the first ten pilot parks, mean habitat quality increased from 0.6677 at pilot onset to 0.6686 in 2020 and 0.6691 in 2023, with the largest gains in Qilian Mountains, Sanjiangyuan, and Giant Panda National Parks (0.14–0.41%). Water retention rose sharply in national parks such as Sanjiangyuan (+129.89%), Hainan Tropical Rainforest (+96.66%), Qilian Mountains (+41.08%), and Northeast China Tiger and Leopard (+39.41%) National Parks, significantly reinforcing downstream water security for rural and urban users. Soil conservation likewise strengthened, with notable increases in Hainan Tropical Rainforest (+39.74%), Sanjiangyuan (+27.86%), Qilian Mountains (+16.31%), and Northeast China Tiger and Leopard (+11.42%). Landscape-scale assessments indicate that the consolidated park system now operates as ecological infrastructure, buffering extreme weathers, reducing erosion risks, and stabilizing hydrological cycles in key upstream watersheds (Luo, 2022; Wu et al., 2023). Across the pre-reform, pilot, and post-reform phases, ecosystem services stabilized during the pilot years and accelerated in recovery after full institutional integration. These trajectories highlight how embedding biodiversity objectives into spatial planning and land-use systems can simultaneously bolster ecological resilience and deliver public goods well beyond park boundaries (Chen, 2021).

Fig. 2. Alpine ecosystem recovery at the source of the Yangtze River, Sanjiangyuan National Park. (Photo by ZHANG Dongxiao)

Enabling inclusive and polycentric governance

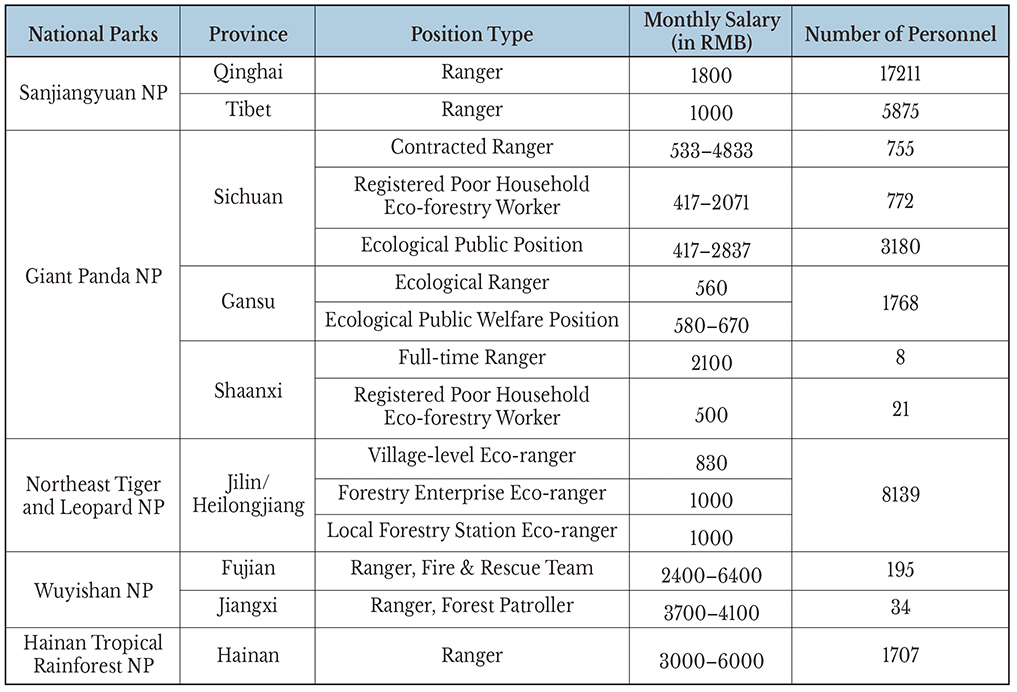

Equally transformative has been the shift in governance dynamics from top-down management to more inclusive, polycentric stewardship. Formerly marginalized in conservation decision-making, local communities are now embedded in park governance through co-management bodies, participatory monitoring, and ecological employment schemes. The ecological ranger program alone has deployed over 50,000 rangers across the first five national parks, channeling 6.7–8.2 billion RMB annually into salaries (Table 1). In rural and high-altitude, economically vulnerable areas such as Sanjiangyuan, these positions have stabilized household incomes, reduced livelihood risks, and played a key role in poverty prevention (Feng et al., 2021). Surveys from Sanjiangyuan indicate rising trust and collaboration between communities and park administrations, especially where benefit-sharing mechanisms and village-level stewardship have been institutionalized (Zhang et al., 2024). In several pilot sites, village councils and trade-off mediation platforms now enable communities to negotiate land-use priorities, resolve conflicts, and contribute directly to conservation planning. At broader scales, reforms have fostered cross-provincial coordination and strengthened central–local policy dialogue, integrating local ecological knowledge into national decision-making. These developments suggest that biodiversity mainstreaming is as much a social and political process as an ecological one—requiring the redistribution of agency, authority, and accountability across governance levels to align conservation objectives with equitable human well-being.

Table 1. Number of eco-rangers and annual financial input in the first batch of national parks

*Data source: Yang, Rui, et al. National Park Livelihood Survey Report (unpublished). 2024.

Challenges Ahead

While the reforms have established a robust institutional foundation for biodiversity mainstreaming, sustaining and amplifying these gains will require navigating the emerging, interlinked frontiers at the nexus where ecological ambition intersects with political economy, governance capacity, and social legitimacy (Huang, 2024). These frontiers define not only the next phase of reforms but also the conditions under which early ecological gains can be secured, scaled, and sustained over time.

Although national parks have become anchors of China’s ecological modernization, their influence outside the conservation sector remains limited. Biodiversity objectives that are firmly embedded in ecological zoning and protected area planning have yet to permeate infrastructure, agricultural policy, and regional economic strategies. Weak cross-sector integration leaves conservation goals vulnerable to displacement by competing land-use demands. Without institutionalized mechanisms to embed biodiversity criteria into transport corridors, energy planning, urban expansion, and fiscal instruments, the policy coherence essential for true mainstreaming will remain out of reach.

Less visible but equally consequential, is the question of adaptive capacity. Consolidating agencies and mandates has yielded a more coherent governance architecture, but its resilience hinges on the ability to anticipate and respond to change. Real-time ecological monitoring, performance-based management, and integrated data platforms remain nascent. Absent accelerated investment in smart regulatory tools, scenario-based planning, and predictable, long-term biodiversity finance, national parks may struggle to adapt to accelerating ecological change and shifting socioeconomic pressures.

Social integration remains an intricate frontier. Although ecological employment schemes and co-management have broadened participation, institutionalization is uneven, and local cultural practices often remain peripheral to decision-making. Embedding indigenous and community knowledge systems, mirroring successful polycentric governance models globally will be critical to reconciling ecological imperatives with the lived realities of park-adjacent communities. Whether national parks are perceived as shared assets or externally imposed restrictions will hinge on achieving this balance.

Get together

China’s national park reforms are more than a domestic policy success, and it is also a living laboratory for embedding biodiversity into the political, economic, and spatial logic of national development. By aligning ecological integrity with governance reforms and social participation, it offers a pathway to biodiversity mainstreaming that is context-specific yet globally resonant. The transition from institutional innovation to deep, system-wide transformation, however, remains unfinished; implementation gaps, sectoral competition, and shifting socioeconomic conditions continue to test the durability of these gains.

For the international community, the value of this experiment lies not in a prescriptive template but in a repertoire of adaptable strategies, integrated spatial planning, consolidated governance mandates, cross-sector policy alignment, and inclusive co-management that can be tailored to diverse political and ecological settings. These principles echo integrative conservation approaches worldwide—different in institutional form, yet united in purpose, seeking to reconcile conservation imperatives with human aspirations through co-produced knowledge, governance, and stewardship.

As nations confront the intertwined crises of biodiversity loss, climate change, and development pressures, China’s state-led yet socially embedded model underscores critical insights: Biodiversity mainstreaming succeeds when institutional ambition is matched with ecological rationality and social legitimacy. The challenge ahead is not to replicate China’s institutional form, but to translate its core principles, coherence, consolidation, and co-production into policy ecologies that are calibrated to local realities. Done well, conservation will shift from isolated enclaves to an organizing principle of sustainable development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by Joint Research Project of Chinese Academy of Sciences and Qinghai Provincial People’s Government on Three-River-Source National Park (E2X2931601), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42230510) and the Second Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (2019QZKK0401).

References

Barraclough, A.D., Reed, M.G., Coetzer, K., Price, M.F., Schultz, L., Moreira‐Muñoz, A., Måren, I. (2023). Global knowledge–action networks at the frontlines of sustainability: Insights from five decades of science for action in UNESCO’s World Network of biosphere reserves. People and Nature 5, 1430–1444.

Bridgewater, P. (2016). The Man and Biosphere Programme of UNESCO: rambunctious child of the sixties, but was the promise fulfilled? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 19, 1–6.

Chen, H. (2021). The ecosystem service value of maintaining and expanding terrestrial protected areas in China. Science of the Total Environment 781, 146768.

Cheng, H. (2024). National protected areas optimization announced: Over 2,500 protected areas withdrawn or merged (in Chinese), http://www.chinadevelopment.com.cn/xc/2024/1104/1918701.shtml.

Eckert, I., Brown, A., Caron, D., Riva, F., Pollock, L.J. (2023). 30×30 biodiversity gains rely on national coordination. Nat Commun 14, 7113. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-42737-x.

Feng, Y., Li, G., Li, J., Sun, X., Wu, D. (2021). Community stewardship of China’s national parks. Science 374, 268–269. doi: 10.1126/science. abm2665.

Folke, C., Biggs, R., Norström, A.V., Reyers, B., Rockström, J. (2016). Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecology and Society 21. https://doi.org/10.5751/es-08748-210341.

Huang, B. (2024). Improve governance system of national parks, build the world’s largest national park system with high quality. Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Chinese Version) 39, 219–229.

Huang, B., Ma, Y., Huang, K., Su, L., Zhang, C., Cheng, D., Wang, Y. (2018). Strategic approach on promoting reform of China’s natural protected areas system with national parks as backbone. Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Chinese Version) 33, 1342–1351.

Li, J., Wang, W., Axmacher, J.C., Zhang, Y., Zhu, Y. (2016). Streamlining China’s protected areas. Science 351, 1160–1160.

Luo, K. (2022). Contribution of ecological conservation programs and climate change to hydrological regime change in the source region of the Yangtze River in China. Regional Environmental Change 22, 10.

Maxwell, S.L., Cazalis, V., Dudley, N., Hoffmann, M., Rodrigues, A.S.L., Stolton, S., Visconti, P., Woodley, S., Kingston, N., Lewis, E., Maron, M., Strassburg, B.B.N., Wenger, A., Jonas, H.D., Venter, O., Watson, J.E.M. (2020). Area-based conservation in the twenty-first century. Nature 586, 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2773-z.

Pörtner, H.-O., Scholes, R.J., Arneth, A., Barnes, D.K.A., Burrows, M.T., Diamond, S.E., Duarte, C.M., Kiessling, W., Leadley, P., Managi, S., McElwee, P., Midgley, G., Ngo, H.T., Obura, D., Pascual, U., Sankaran, M., Shin, Y.J., Val, A.L. (2023). Overcoming the coupled climate and biodiversity crises and their societal impacts. Science 380, eabl4881. doi: 10.1126/science.abl4881.

The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. (2021). Biodiversity Conservation in China.

Wang, Y., Hu, Y., Liu, J. (2024). Overview of China’s national park system reform process. Chinese Journal of Population, Resources and Environment 22, 481–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjpre.2024.11.011.

Whitehorn, P.R., Navarro, L.M., Schroter, M., Fernandez, M., Rotllan-Puig, X., Marques, A. (2019). Mainstreaming biodiversity: A review of national strategies. Biol Conserv 235, 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.04.016.

Wu, H., Yu, L., Shen, X., Hua, F., Ma, K. (2023). Maximizing the potential of protected areas for biodiversity conservation, climate refuge and carbon storage in the face of climate change: A case study of Southwest China. Biological Conservation 284, 110213.

Wu, J., 2023. Wild life populations increase thanks to national parks, www.globaltimes.cn.

Wu, R., Hua, C., Yu, G., Ma, J., Yang, F., Wang, J., Jin, T., Long, Y., Guo, Y., Zhao, H. (2020). Assessing protected area overlaps and performance to attain China’s new national park system. Biological Conservation 241, 108382.

Xinhua News Agency. (2024). China makes headway on biodiversity protection, www.gov.cn.

Xu, H., Cao, Y., Yu, D., Cao, M., He, Y., Gill, M., Pereira, H.M. (2021). Ensuring effective implementation of the post-2020 global biodiversity targets. Nat Ecol Evol 5, 411–418. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-01375-y.

Xu, W., Pimm, S.L., Du, A., Su, Y., Fan, X., An, L., Liu, J., Ouyang, Z. (2019). Transforming protected area management in China. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 34, 762–766.

Xu, W., Xiao, Y., Zhang, J., Yang, W., Zhang, L., Hull, V., Wang, Z., Zheng, H., Liu, J., Polasky, S., Jiang, L., Xiao, Y., Shi, X., Rao, E., Lu, F., Wang, X., Daily, G.C., Ouyang, Z. (2017). Strengthening protected areas for biodiversity and ecosystem services in China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 1601–1606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620503114.

Yang, Z. (2024). NPC initiates law to protect national parks, in: Zekun, Yang (Ed.), China Daily.

Zhang, H., Wan, X., Pan, H., Wang, Z., Pan, R., Li, B., Wei, F., 2025. Tracing the Path to Extinction: Long‐Term Impacts of Human and Environmental Factors on Tiger Survival in East Asia. Integrative Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1111/1749-4877.12998.

Zhang, L., Luo, Z., Mallon, D., Li, C., Jiang, Z. (2017). Biodiversity conservation status in China’s growing protected areas. Biological Conservation 210, 89–100.

Zhang, P., Zhao, J., Krott, M. (2023). Strictest nature conservation: China’s national park policy underpinned by power shift and turf dynamic. Forest Policy and Economics 154, 103033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2023.103033.

Zhang, Z., Wei, Y., Tang, L., Wang, Z., Hu, X., Li, X., Bi, Y., Huang, B. (2024). Co-management enhances social capital and recognition of protected area: Perspectives from indigenous rangers on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J Environ Manage 372, 123346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.123346.

* Correspondence may be addressed to ZHANG Huizhi at zhanghuizhi@sina.com and HUANG Baorong at huangbaorong@casisd.cn.

1. PhD candidate at the Institutes of Science and Development, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). His research interests focus on policy interventions and social-ecological processes, systems integration and sustainability, etc. E-mail: zhangzhi@casisd.cn.

2. Professor and Academic Director of the Institute of Sustainable Development Strategy under the Institutes of Science and Development, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). His research interests focus on governance system of national parks and protected areas, strategy and policy of ecological conservation, etc. E-mail: huangbaorong@casisd.cn.